Sustainable Destinations Protecting Nature and Traditions: Regional Tourism in Higashimatsushima and Tono

In the Tohoku region, various efforts are being made to protect nature and tradition while working toward a sustainable society. After recovering from the disaster, Higashimatsushima City in Miyagi Prefecture has been developing eco-tourism that leverages the region’s unique attractions, contributing to the creation of a sustainable tourism destination. Meanwhile, in Tono City, Iwate Prefecture, tourism focused on the region's history and culture is gaining attention. The natural environment, folklore, and traditional lifestyles of Tono are being preserved as "Tono Heritage," with local residents actively working to safeguard them. These efforts aim to utilize the region's culture as a tourism resource, while ensuring its continued preservation as part of sustainable tourism. Both regions are building upon past experiences to aim for sustainable development in the future.

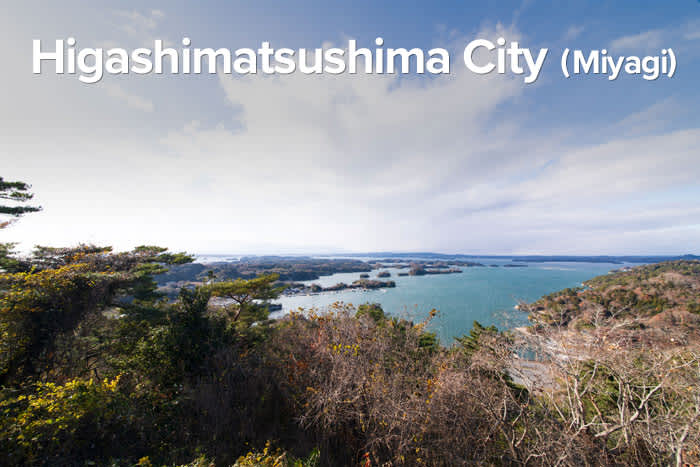

Higashimatsushima City (Miyagi)

Higashimatsushima: A Journey Through Resilience and Renewal Exploring its Timeless Beauty, History, and Sustainability Efforts

Sustainability Spotlight

Hideki Sekiguchi

Higashimatsushima City Reconstruction Town Development Promotion Officer

Born in 1968 in Ota Ward, Tokyo, Hideki Sekiguchi was captivated by the people and nature of Higashimatsushima City when he visited as a disaster relief volunteer during the Great East Japan Earthquake. This experience led him to relocate to the area. From 2016, he spent three years serving as a regional revitalization volunteer, focusing on forest management and working as a tour guide. Currently, as a reconstruction town development coordinator, he is dedicated to developing trekking routes, such as the Miyagi Olle Oku-Matsushima course centered around Miyato Island, and providing guided tours while promoting sustainable tourism.

Higashimatsushima in Miyagi Prefecture is a rural area between the mountains and the sea. This area has a lengthy history, with a wealth of remains from the Jomon period (10,000 and 300 BCE) when the first hunter-gatherers settled here, and evidence that Date Masamune, a famous 17th-century samurai spent significant time here. It’s also known for a modern event that shaped Japan. In 2011, it was one of many places in eastern Tohoku that was deeply damaged by the Great East Japan Earthquake, the largest ever recorded in Japan, and the subsequent tsunami, which devastated the area.

Since then, the community has rallied to revitalise Higashimatsushima, using local resources and sustainable energy to nurture a hub for ecotourism. These efforts have earned it a spot in the Top 100 Sustainable Destinations worldwide. It has also been designated as an Environmental Future City and an SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals) Future City.

Listen in detail about Miyagi Olle

Hideki Sekiguchi, who relocated from Tokyo, is serving as the Higashimatsushima City Reconstruction Town Development Promotion Officer as part of the reconstruction plan for this area. I met him for a guided tour of the Miyagi Olle which he led the development of. I was unfamiliar with the concept of an “olle” until he explained that the term comes from the Jeju dialect in South Korea, meaning “a small alley leading to a house from the street”, but has evolved into a term for trails that pass through nature and residential areas.

Walking up Mt Otakamori

The route differs from more traditional trails by taking in a variety of local landscapes, offering an insight into the lives of people who live and work here, as well as tourist sights. We walked a forested incline as he told me about his love for the area. “Over time, I realised that these landscapes, the local food, traditions and culture are very important to people,” he said. This local passion kept him inspired to develop the town and its trails to encourage more people to discover the area.

Matsushima Bay, one of Japan’s three most scenic spots

A beach that has been redeveloped for locals to enjoy

He sprung to the top of Mt. Otakamori (105 meters) with the ease of a mountain goat. At the peak is a large observation deck with views across Matsushima Bay and its many pine-covered islets. The Bay is considered one of Japan’s top three most scenic spots, along with Amanohashidate, a pine-covered sandbar in Kyoto Prefecture and Miyajima, known as Shrine Island in Hiroshima Prefecture. Once I’d had a few minutes to take in its beauty, he asked me to pivot 90 degrees to the right where he gestured at swathes of barren land. “This was all covered with houses, but since the tsunami washed them away, the area has been left untouched. It won’t be rebuild upon,” he says. The juxtaposition of such beauty with this sparsity, still scarred from the events of 2011, was jarring and incredibly moving. It’s easy to think of that time as a long time ago, but in many areas of Tohoku, it still affects their daily lives.

A temple along the Miyagi Olle

We continued on the olle, which features historic shrines, coastal views, forested paths, rural villages and even ancient Jomon shell mounds, where Jomon period people would discard shells, pottery and bones. These shell mounds act like time capsules, showing us what Jomon people ate and how they lived.

A pretty islet along the trail

The Miyagi Olle includes an array of landscapes, giving an idea of everyday life

Perhaps my favourite part of the olle was walking through rural residential areas. After the tsunami, the population of Miyato Island decreased from about 1,000 to about 400, so there are very few houses here; nevertheless, wooden farmhouses, rice fields, pretty gardens, and charming walkways dot the route. My city girl heart was warmed by an interaction with a local who offered us some dried persimmon I had admired hanging in his windows. These sights and conversations are the kind that only a quiet, rural location can offer; a genuine insight into everyday life.

Forested trails along the olle

Dried permissions offered by a local along the olle

We ended the day at Okumatsushima Jomon Village Museum where I learned more about the shell mounds we’d just seen. “Shell mounds are often inaccurately referred to as trash heaps,” the museum deputy director told me, “However, they were far more significant than this. We know from finding human and animal remains, discarded tools and evidence of rituals within them that they were more like a sacred place of departure.” Excavation of these shell mounds also tells us that eight tsunamis struck this area from the Jomon period to the Edo period (1611). “It’s proof of the resilience that is so deeply ingrained in the community,” said the museum deputy director.

A shell mound in the Okumatsushima Jomon Village Museum

Discovering more about the Jomon Period

The next morning, we headed to Ohamada Wetlands. There were 41 houses and farmland here before the 2011 tsunami destroyed them. Now, the area has been left to flourish as a nature spot to conserve the landscape and nurture biodiversity for future generations. In the years since the tsunami, several plant species that were previously thought to be extinct have been discovered, and dragonflies, ospreys, eagles and black kites have all thrived here.

A black kite flying over the wetlands

The Ohamada Wetlands are home to species previously believed to be extinct

A name that came up repeatedly during my time in Higashimatsushima is C.W. Nicol (1940 - 2020), a British-born naturalised Japanese author and conservationist who taught the power of nature to heal those traumatised by disaster. Hideki first mentioned him to me for his wisdom on the environment; that danger existed in the form of wild animals and natural disasters, but that we must learn to adapt and live with them. His name came up again as I headed to Suzaki Wetlands, a habitat that has been restored post-earthquake that now serves as a resting place for migratory birds, with ongoing efforts to remove invasive species and improve water quality.

The community are working hard to see the Suzaki Wetlands thrive

Birds flying over the wetlands

Seeing three years of work the community has put into these wetlands

C.W Nicol saw the potential of Higashimatsushima as a place to preserve wetlands and develop ecotourism. The idea was spurred after he saw thousands of swans, geese, ducks, coots, cormorants, gulls, ospreys and herons happily wallowing in the flooded rice paddies. He set the wheels in motion for the Suzaki Wetlands, which he called his “last lifework”. After his passing, the Higashimatsushima community rallied to keep developing the area, building waterways that connect the wetlands to the sea to encourage more biodiversity, piping out deoxygenated water to avoid stagnation, and planning to establish a visitors centre and a café in the future.

Birds enjoying the wetlands

As we climbed up the side of a bank to look over the wetlands, I was awestruck at the thousands and thousands number of birds I saw flying overhead and bobbing on the water. I have never seen so many all at once. C.W Nicol would be so proud of his legacy here.

Out of something so devastating, the Higashimatsushima community has taken a considered approach to rebuilding by working with nature to create a sustainable environment. The region's history and its community-minded recovery efforts offer visitors a profound narrative of survival, adaptation, and hope.

Higashimatsushima extends an invitation to witness a living story of perseverance and renewal. Whether exploring the thoughtfully designed olle trails, admiring the breathtaking Matsushima Bay, or learning about the Jomon people, visitors will leave with a greater appreciation for the interconnectedness of people, history, and the natural world.

Tono City (Iwate)

The Future of Tono: Shaped by Community Pride and Sustainability Heritage and Modern Sustainability in Tono's Storied Landscapes

“Immersive travel” and “living like a local” are experiences often sought by intrepid explorers. But finding those authentic connections and activities can be difficult in a country where you don’t speak the language or understand the culture. However, the people of Tono, a small mountainous region in Iwate in northeast Japan, have made it their mission to welcome people to discover their way of life; stay in their homes, hear the folk stories they tell, eat locally-grown food and understand the value of the things their community holds dear. This community-centered approach to tourism has earned the area recognition as one of the Top 100 Destination Sustainability Stories for 2024..

Sustainability Spotlight

Haruka Tada

Sustainability coodinator at Tono Furusato Shosha Co.,Ltd(DMO) / Tono Furusato Tourism Guide

Born in 1990 in Tono, Iwate Prefecture. After majoring in cultural anthropology and studying abroad in Cuba, she worked at an IT company in Tokyo before returning to Tono in 2018. As a coordinator for Next Commons Lab Tono, she has supported new residents and created opportunities to pass down cultural traditions. Since 2020, she has also served as a bilingual local guide and coordinator, working toward developing a sustainable tourism community.

I travelled to Tono to meet Haruka Tada, a Tono Furusato Tourism Guide, and learn about the strategies she has helped implement that have put Tono on the map as a benchmark for sustainable travel. We met at Tono Furusato Village, an open-air museum that features thatched houses dating back around 250 years.

Tono Furusato Village

She introduced me to a craftsman who uses rice straw to create ornamental horses, wreaths, snow shoes and more. He led me into one of the houses, where a sunken hearth warmed the room and made it smell a comforting wood fire smell. He demonstrated the basics of creating a straw rope, using my hands to roll the straw into strands, which I then twisted together, in an almost meditative process. To pass on his skills, he conducts regular workshops in the village.

Learning straw craft

Learning straw craft

Straw horses

Elsewhere in the village, she pointed out the small stature of a kappa, a water-dwelling creature from folklore that has a humanoid body, with a tortoise-like shell on its back. These mischievous water deities are famous throughout Japan but are particularly synonymous with Tono, an area long known for its legends thanks to The Legends of Tono, a book by folklorist Yanagita Kunio published in 1910.

A kappa water deity

Tono’s storytelling heritage is still foundational to the area. “The best way to understand the people and the appeal of Tono is to find out about it through the stories and interactions of locals,” she told me.

Hearing about the Tono Heritage

As we embarked on a tour of the local area, she told me about the Tono Heritage Recognition OrdinanceTono, a program that, for the past 18 years, has worked to catalogue and protect local treasures that are meaningful to the community. Cultural properties are nominated by the community and given money to maintain.

Ultimately, the mayor has the final say on what is certified as Tono Heritage, but the process is a rare example of a community working from the bottom up, rather than top down, which, she explained, helps build a sense of community and makes locals more aware of and proud of their local treasures and ensure the next generation want to continue to maintain and preserve them.

Hearing an explanation of the importance of each stone

She next took me to meet a local, Mr. Kumagai, the representative of the group that maintains Tono Heritage No. 17, the Hiwatashi Stone Monument Group, a collection of seven stones, in front of a particularly beautiful rice field. He explained that each one has its own meaning, reflecting Tono’s community values. One is a monument to horses, which were used for farming and transportation and are very important to the area, and it is dedicated to praying for health and safety, while another represents a memorial for any visitors who have died whilst in the area.

Aragami Shrine

A little further down the road, we visited Tono Heritage No.37, Aragami Shrine, a small and picturesque thatched shrine that straddles two rice fields. Locals have prayed at this shrine for generations, so despite being privately owned, it has been designated a Tono Heritage site.

Tono Heritage No.145, Unedori Daimyojin Shrine

Unedori Daimyojin Shrine

Red fabric strips at Unedori Daimyojin Shrine

The first snow of the season began to fall as we hiked a trail to Unedori Daimyojin Shrine. This pretty wooden shrine is surrounded by cedar trees decorated with hundreds of red fabric strips which visitors have traditionally attached to the shrine to pray for marriage.

A carved face at Gohyaku Rakan, Tono Heritage No.162

Gohyaku Rakan

Carved faces at Gohyaku Rakan

Next along the hike was Gohyaku Rakan, which Tada called “an open-air temple”. We ascended a forested incline, surrounded on both sides by large mossy stones, each with serene faces carved into them. She explained that, in the mid to late 1700s, the Great Tenmei famine led to thousands of deaths in the region. “To console the spirits of those who died, a local priest carved Buddha faces into 500 rocks here,” she says.

Walking up to Hodohora Inari Shrine, Tono Heritage No.146

Hodohora Inari Shrine torri gate

Hodohora Inari Shrine

The final Tono Heritage site we walked to on the trail was Hodohora Inari Shrine. We walked uphill through a fairytale-esque forest, and I began to see why folklore stories thrived here. The shrine at the top is filled with phallic carvings in wood and stone which symbolise fertility, so it’s a pilgrimage hopeful parents make.

Agriturismo Omori-ke, a 70-year-old farmhouse

After a fulfilling day, she recommended I stay the night at a local farm. Agriturismo Omori-ke is a 70-year-old farmhouse where the owner was born and raised.

Chatting with the owner

Staying here gives you a glimpse into life as a local in Tono; chatting with the owner about her life, helping her harvest vegetables from her farm before prepping them for my next meal. While she doesn’t speak much English, we used her voice translator to discuss everything from music to Tono folklore. We even sang a little karaoke together as we indulged in local beers.

Outside Agriturismo Omori-ke with the owner

Just as Tada had said, speaking with a local about the traditions imbued my experience in the area with much more meaning. Over dinner, the owner told me that she thought folklore helped to strengthen the community. She said that in cold months, people make up stories to keep themselves entertained and that, any problems the community had would be blamed on monsters rather than other people, which helped foster a harmonious community.

There are around 20 homestays in Tono, some of which are with farmers, others with housewives or hairdressers, but each gives a sense of daily life in this corner of northern Japan.

Tourism in Tono offers more than just a glimpse into rural Japanese life; it invites you to become part of a living tradition, where its people, history, and nature form the foundation of a sustainable future. Tono’s charm, and the pride of its community, stem from its people and the stories they tell about the local heritage they hold dear.

This community-orientated tourism exemplifies how a community’s pride in its traditions can create a meaningful experience for visitors and establish a tourism industry that benefits and enriches visitors and locals alike.

Links