Yambaru National Park covers most of the three villages that make up the northernmost part of Okinawa island, an area home to one of Japan’s largest subtropical evergreen broad-leafed forests. The park is a haven for many species found nowhere else on earth, including the Okinawa woodpecker and the flightless Okinawa rail or yambaru kuina.

Between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, when Okinawa was united as the Ryukyu Kingdom, Yambaru supplied charcoal and timber to central and southern Okinawa Island under the management of royal officials and local communities. Today, the borders of Yambaru National Park encompass settlements in the villages of Kunigami, Ogimi, and Higashi, reflecting this history of coexistence with nature. The local culture includes distinctive regional festivals given in prayer for a bountiful harvests and rituals appealing to the sea deity (unjami or ungami) to fill the local fishing nets.

We spoke to Hiromi Kamigaichi of Okinawan tour and travel experience company Endemic Garden H, about what makes Yambaru unique and how to make a visit to the park more enjoyable and meaningful.

An Island Haven, Isolated But Not Untouched

“When people hear that Yambaru was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List because of its biodiversity, they tend to imagine an unspoiled wilderness,” says Kamigaichi. “But Yambaru reflects its centuries of human habitation in many ways, and this is the context in which the area’s unique ecosystems were preserved.”

Okinawa was part of the mainland until around 12 million years ago, with the current Ryukyu Archipelago arriving at its current form by around 2 million years ago. This geological history left Yambaru with stunning coastal geography and an ecological treasure trove of plants and animals that continued to evolve in isolation. Yambaru is home to thousands of unique animal species, including birds like the Okinawa woodpecker, yambaru kuina, and Ryukyu robin, as well as insects and amphibians.

“One reason these species have survived in Yambaru is because the forest’s ecosystem originally had no carnivorous mammals,” says Kamigaichi. This changed around a century ago, when the mongoose was introduced to Okinawa in an attempt to reduce harm caused by habu viper bites. Unfortunately, the plan went awry: because mongooses and pit vipers are active at different times of day, the two species seldom encountered each other, and other animals like the flightless yambaru kuina fell prey to mongooses instead. Today, the mongoose is the highest-profile target of efforts to eliminate invasive species from the park, with organized groups like the Yambaru Mongoose Busters leading the charge.

“However, in terms of dealing with and raising awareness about invasive species, most of my energy is focused on invasive flora,” says Kamigaichi. “Plants don’t directly kill off native species like predatory animals do, but if they crowd out the region’s local flora, the animals that depend on those plants suffer, too. In that sense, they undermine the whole foundation of the ecosystem.”

The Human Side of Yambaru

Yambaru has long had human residents as well. “People settled near water sources like rivers, which were central to the life of the village,” says Kamigaichi. “The water was used to bathe newborn babies and purify the dead. A village was thought to extend beyond the structures and cleared land to include the water that nourished it.”

In the days before modern conveniences, the Yambaru forest supplied all the resources needed for everyday life. “Firewood and charcoal were used for cooking, and instead of ropes and cords, people used vines, with different thicknesses chosen for different purposes,” explains Kamigaichi. During the Ryukyu Kingdom’s heyday, the residents of Yambaru felled trees in the forest and then hauled them to shore, where they were shipped south down the coast to the kingdom’s capital. The forest changed considerably from its original state, but Ryukyu officials like Sai On made sustainable management a priority, ultimately leading to the creation a new ecosystem in which humans could coexist with the existing plant and animal residents.

Belief systems were also shaped by this harmonious coexistence, with yearly festivals to pray for bountiful crops and fishing catches. Some of these are now considered Intangible Cultural Heritage, like Shinugu in Ada.

Enjoying a Visit to Yambaru

“Some people assume that because Yambaru has such high biodiversity, exotic flora and fauna must be on ready display everywhere,” says Kamigaichi. “Unfortunately, that isn’t the case. Many of the forest’s animal inhabitants are tiny and shy, and there’s no guarantee you’ll see any of them in particular—but walking with a guide is a good way to maximize your chances of a memorable encounter.” Some guided tour companies have employees who can offer tours in English and other languages, but this must usually be requested in advance.

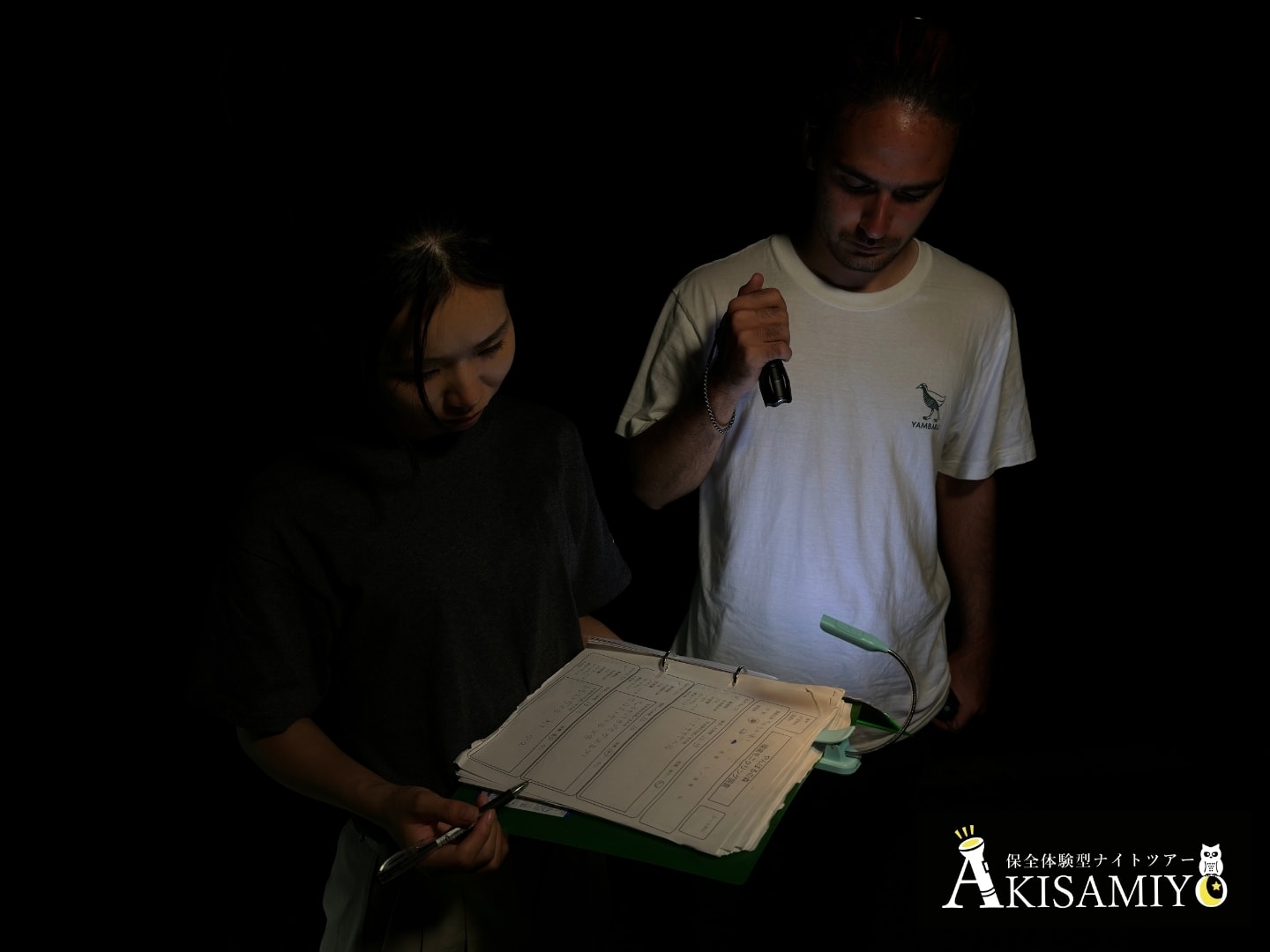

Night tours are also popular, with the chance to see nocturnal species and choruses of frogs and insects adding to the atmosphere. Akisamiyo, an initiative from the Higashi Village Tourism Promotion Council, is more of a night nature watch than a night tour. “You can tell what season it is by which frogs are calling,” says Kamigaichi. “When I run a night tour, my goal isn’t to point out endangered species—it’s to help my clients see the species that are so close at hand that they are often overlooked. We spend three hours walking slowly along a course that could be walked in one.”

A guided tour also eliminates the risk of accidentally straying from the trail or walking into areas off-limits to visitors. Yambaru Discovery Forest has a network of clearly marked and highly scenic trails—but even here, walking with a guide is the best way to make sure you don’t miss out on anything.

Understanding the history of the Yambaru forest and its human stewards allows a deeper appreciation of what this fragile ecosystem has to offer the world.

Doing Your Part to Protect the Park

- Since Yambaru National Park includes multiple villages, some routes go past private residences or sacred sites called uganju. Avoid entering private property or sacred sites, and ask permission before taking any photographs.

- Help protect Yambaru’s ecosystem by not bringing any flora or fauna into the park—including seeds, fruit, and so on—not leaving any garbage behind you, and not taking any plant or animal products with you when you leave.

- Never leave the trail when walking in the forest, both for your own safety and to avoid harming any flora or fauna.

- There are almost no public toilets along the trails, so be sure to avail yourself of the facilities at a visitor center or roadside station before you begin hiking.

- When driving in Yambaru, drive slowly and carefully. Small birds may take flight from the ground and small animals often dart across the road.