Setting the Table in Style Explore the world of Japanese folk craft tableware and make your own!

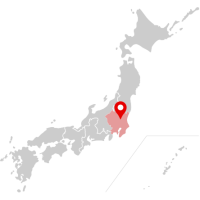

Mashiko Town, Tochigi Prefecture - Kanto

Whether for formal dining uptown or a quick ramen downtown, Japanese tableware is an inseparable part of the Japanese culinary experience. The more time you spend eating in Japan, the more you realize that the country has a bewildering array of tableware shapes, sizes, and styles. And just when you think you have seen it all, something different comes along to surprise you!

This is not happenstance, and while you might think that the restaurant is trying to impress you with its discriminating taste in tableware, more likely it is simply bringing local ceramics to your table. To the restaurant then, the tableware is just whatever can be obtained in the immediate vicinity, but to the traveler passing through different prefectures with short stops here and there, the diversity and artistry of each item seen and sometimes used along the way is more apparent.

Usually referred to by its place name followed by the word “yaki” (ware), Japanese ceramics can tell you a great deal about the region where they are made, but you can go one step further and actually participate in the pottery story yourself.

Culture of Inclusivity

Located deep in the rolling hills of Tochigi Prefecture to the north of Tokyo, the town of Mashiko is a little different from other pottery capitals, and its pottery, Mashiko ware, is also a bit unusual in the world of Japanese ceramics.

In many regions of Japan, strict rules are in place to ensure that pottery culture remains local. A person cannot suddenly decide to become a potter but rather must be born one. An alternative is to enter the profession as an apprentice, but the training is long and hard, and apprentices are not allowed to work with the best-quality clay until they have proved themselves. This may seem like a practice from a bygone era, but it is current reality for many potters and the reason why there are lineages stretching back centuries, working at the same kiln as the forebears.

Mashiko has a shorter history than many of Japan’s more famous pottery towns, dating back to the latter half of the Edo period (1603–1867). Located relatively close to the rapidly expanding city of Edo (modern Tokyo) with deposits of excellent-quality clay nearby in the local mountains, Mashiko experienced a renaissance that catapulted it from small temple town to pottery powerhouse.

Contributing to the town’s rapid expansion into pottery was its welcoming attitude toward outsiders, which attracted hundreds of different artists who were soon working side by side in the town, a tradition that continues to this day. Quintessential Mashiko ware is on the rustic side, giving prominence to the clay itself, but because of the accepting attitude of the town, many different styles of the pottery have flourished.

A transition from supplying functional pottery to Tokyo to creating more artistic works occurred in the early twentieth century. Around that time, Mashiko master potter Hamada Shoji brought to Japan the artistic inspiration and energy he had acquired through his experiences with the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain. Along with the art critic Yanagi Soetsu, Hamada started the mingei (folk craft) movement, and soon Mashiko ware began to receive the recognition it deserved. Hamada himself was eventually designated as the first Living National Treasure in Japan for his contributions to culture.

The tremendous passion for pottery continues in Mashiko to this day, and there are over 250 potteries and around 50 specialist ceramic shops and galleries located there. Wherever you look in town, you will find Mashiko ware with its distinctive earth tones. There is also a biannual pottery fair in spring and autumn where over 500 potteries and dealers of antique Mashiko ware take over the town center for an extended festival of all things pottery.

Be Part of the Mashiko Story

As you might expect to find in a town that has traditionally welcomed outsiders, there are plenty of places where you can try your own hand at making Mashiko ware. Yokoyama Tougei is one such place, and it also offers atelier tours where you can discover the complexities hidden beneath the surface of Mashiko ware.

Mashiko ware is either sculpted using the hands and a variety of Japanese tools or thrown on a low potter’s wheel. The clay you will use in the workshop is of the same quality as that used in the masterpieces created by the Living National Treasures. You should not be disappointed, however, if the piece you create does not look quite like those of the professionals, given their extensive practice (and their talent, of course!).

The good news is that all your failures while learning the ropes can be undone, and the clay kneaded again and reused by you or someone else. Over the course of an hour, you can make quite a number of pieces and then choose the ones you want to be fired.

Under the guidance of a Mashiko-ware artisan, you will go from learning the basics of pottery to creating designs with your choice of glazes from among the many traditionally used in Mashiko ware.

With your newly acquired knowledge of form, detail, and glazes, you should have nearly all the skills you need to create the perfect ceramic piece—now you just need to steady your hands and get going!

Your finished work must sit for a couple of days before having its base leveled, and then it has to dry for a month before it can be glazed and fired in the kiln. International visitors can arrange to have their work sent on to them, so although you must wait a bit, you will have a very nice surprise when your box of pottery turns up at your home! Any attempt to speed up the drying process risks the integrity of the work, so patience is essential.

Mashiko Ware in Use

The difference between mingei (folk craft) and fine art is, broadly speaking, that fine art is considered complete upon creation whereas folk craft is not considered complete until it is put to use. The same could be said of most artisanal crafts—a vase can perhaps be more admired when filled with flowers, and thus fulfilling its intended purpose, than when it is empty.

The same is true of Mashiko ware and Japanese tableware as a whole. It may be beautiful on its own, but if you put it to use, you can truly understand it.

When you are in Mashiko, the thing to eat is soba noodles, a favorite in mountainous communities. Local buckwheat and pristine water give Mashiko’s soba noodles such a distinctive character that they have been named Mashiko Soba, and of course, they are served on local pottery—what else?

To complete a flavor tour of the area, be sure to try the local vegetables, served as tempura (above). And grated yam (tororo) on top of rice is another popular dish. Tororo is also frequently served with the soba noodles, and it is one of the most nutritious dishes going.

Into the Heart of Ancient Mashiko

Now that you are well fed, it is time to head up into the hills and back into Mashiko’s history. Long before Mashiko ware was the town’s most famous export, Mashiko was known for its temples, especially Saimyoji, which dates back to 737.

Also known as Tokko-san Fumon-in, Saimyoji belongs to the Buzan sect of the Shingon school of Buddhism and was built by forebears of the Mashiko family, from whom the town would later take its name.

It is a pastiche of architectural styles from many eras, with most of the original structures having been destroyed by fire at one time or another, like many temple buildings in Japan. The Tower Gate dates from 1492, and the Three-Storied Pagoda from 1538—both are rare in that they blend Chinese Tang-dynasty with Japanese architectural styles.

The Main Hall houses the principle icon, the Eleven-Faced Kannon Bosatsu, as well as a number of national treasures. When you visit the hall, your proximity to these fantastic religious sculptures offers you an exceptionally rare encounter with the arts, or the spiritual, depending on your viewpoint. This is a must-see for those interested in Buddhist statues.

But the crowning glory is yet to come in the Enma Hall, where the great Laughing Enma awaits. Enma (also known as Emma) is the king of the underworld in Buddhism. Flanked by his two court attendants, he dispenses justice to everyone called before him. Those who have received enlightenment in life will escape that fate, but everyone else will face Enma. And if a period in hell is demanded, it will be administered by the laughing face of Enma.

Saimyoji’s Enma and its surrounding statues date back to 1714, and the main statue of Enma is considered to be the largest depiction of the figure in Japan. The scale is certainly daunting, as is his taunting pose as he leers at you. While he is called the Laughing Enma, there are many interpretations of his expression, some reading it as shouting or as a fearsome scowl—you will have to stand in his presence to decide for yourself.

Hidden in the hills and fields of Tochigi Prefecture, Mashiko is a treasure trove of diverse arts and crafts and is ready to reward those who step off the beaten path.

Contact Information

Yokoyama Tougei

3527-7 Mashiko, Mashiko-machi, Haga-gun, Tochigi 321-4217

Roan Soba

3580-2 Mashiko, Mashiko-machi, Haga-gun, Tochigi 321-4217

The Temple Saimyoji

4469 Mashiko, Mashiko-machi, Haga-gun, Tochigi 321-4217

How to Get There

Located in the southeastern part of Tochigi Prefecture closest to Tokyo, Mashiko is surprisingly accessible by public transport. You can get there within three hours by train leaving from Ueno and changing at Shimodate. However, if you use the Kanto Yakimono Liner, a bus that departs from Akihabara in central Tokyo, not only will you get there direct in just over two hours, but you will pay a fraction of the train fare. The bus is without a doubt the best option for day-trippers. Once you are at Mashiko Station, you can comfortably walk to most of the popular destinations, and bike rentals are also available within the station.

Recommended Itineraries

Mashiko is a popular day-trip destination from Tokyo, but it is also easy to include in itineraries for the popular destinations of Utsunomiya, Nikko, and Nasu. Tochigi Prefecture as a whole allows for some serious outdoor adventures in Nikko National Park, but it also offers more relaxed activities, like fruit picking and walking, that don’t require as much preparation.

Once you are in Mashiko, you can find lots to do besides shopping for or making pottery, such as visiting the historic Higeta Indigo Dyeing Studio in the center of town, touring around the numerous historic temples and shrines, or sipping sake at one of the breweries there.

Related Links

Mashiko Town Tourist Association (English)

Map

Featured Cuisine

Japanese cuisine concerns not only the edibles on the plate but also the plate itself. Representing the local produce, the changing seasons, and culinary aesthetics is a function of the tableware as much as the food itself. Accordingly, wherever you go in Japan you will encounter ceramics and porcelain that are in tune with local tastes as well as the environment. Furthermore, the local cuisine presented on the region’s own tableware provides clear insight into the identity of that region. Whether you intend to collect it or just admire it, be sure to take the time to appreciate the tableware the next time you enjoy a meal out.

-

Author

Author: Samuel

Originally from the UK, Samuel studied Japanese Studies in the UK before completing his post-graduate studies in Japan. Now with over a decade of writing about Japan for a number of publications, and teaching about Japanese art and design at university, he hopes to bring his love of Japan to a wide audience. His favorite Japanese food is takoyaki as the perfect street snack.

All information is correct as of the time of writing.

Please check for the latest information before you travel.