Masters Series: Part One The Art of Japanese Tea Ceremony

Running deep within Japan’s rich culture, the tea ceremony tradition has remained a cherished ritual for centuries, serving to bring people together in an environment of tranquillity to enjoy freshly whisked matcha tea. Head Priest of Jikoin Temple in Nara Prefecture, Mr Jyokun Ozeki, shares his extensive knowledge on this classic art form and a backstage pass to Jikoin.

Also known as the ‘tea ceremony temple’, Jikoin was designed specifically in the 17th century as a place for the ceremonial preparation and presentation of matcha for tea gatherings. Today, it is Mr Ozeki who keeps these traditions alive at Jikoin, conducting many of the tea ceremonies himself.

Photo Credit: Nara-Jikoin Temple

We understand Jikoin Temple has been in your family for a few generations and you grew up here. When did you first start studying chanoyu (tea ceremony)?

Yes, I grew up here and am the current head priest. Jikoin has been managed by a long line of priests dating back over 350 years – I’m actually the 21st! However, I am the first son to have inherited Jikoin from his father. Before then, management of Jikoin passed from one priest to another. Traditionally, Buddhist priests were not permitted to marry, but this changed over time and some temples are now managed by the one family. I actually started studying tea under a master in Osaka when I was 17.

Photo Credit: Nara-Jikoin Temple

Having lived here all your life, is there one part of Jikoin which is particularly special to you?

Jikoin was established in 1663 by the daimyo (feudal lord) Sekishu Katagiri. He specifically designed it as one large ‘tearoom’. From the entrance gate and cobblestone path through the woods to the main hall and small teahouses – all elements combine to create a unique atmosphere. It's the oldest and one of the few remaining tea ceremony temples left in Japan. If I must choose a favourite part, I’d probably have to say the cobblestone path. It marks the transition from the outside world and builds anticipation as guests emerge from the woods into the main compound.

Photo Credit: Nara-Jikoin Temple

Can you tell us a little more about how Jikoin was specifically designed for tea ceremony?

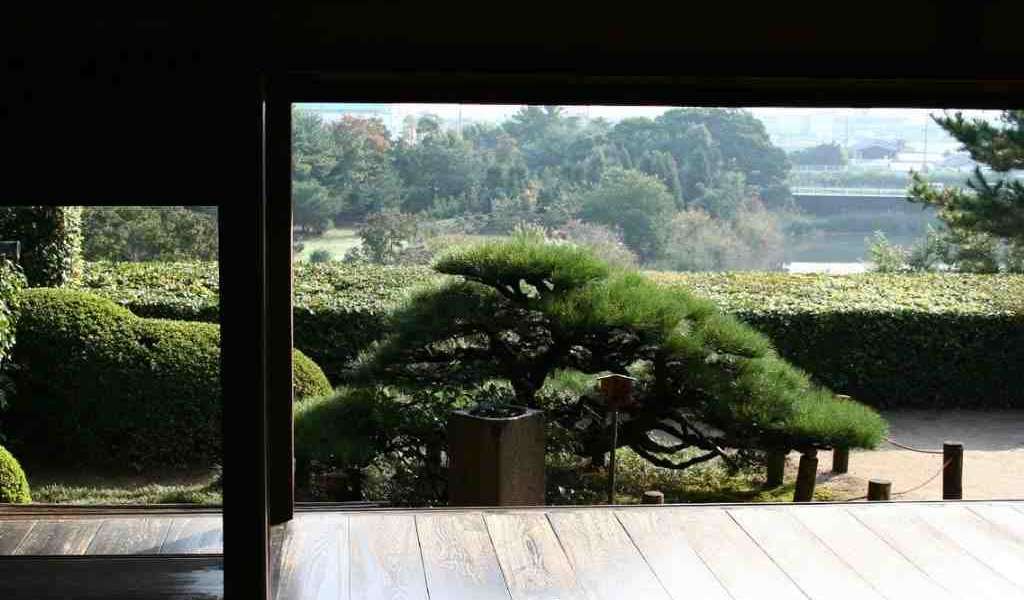

For me, the perfect place for chanoyu is a place where people can relax and clear their mind. Our main hall here is open, bright and quite simple in design – a bit like a traditional farmhouse. The garden also matches that aesthetic with trees you would find in the local woods, nothing exotic. The resulting effect is a sea of green, which visitors find instantly calming. The open partitions let in the breeze and the sound of cicadas and birds (and the odd wandering insect!), creating a total sensory experience.

In tea gatherings held here during the Edo Period (1603-1867), guests would stay for the day. As the chanoyu places great emphasis on hospitality, the host would plan the event in great detail. Different rooms would be used and different styles of tea, beverage and food would be served. Guests would relax in the large zashiki room where they could appreciate the garden, enjoy the breeze and converse with others. To create a different mood, guests would retire to smaller tearooms where the atmosphere is more intimate and subdued, allowing for a different kind of conversation and reflection. Fundamentally the day was planned to deliver omotenashi (wholehearted hospitality), where the host would consider the comfort of each guest to create an atmosphere of relaxation and tranquillity.

Photo Credit: Nara-Jikoin Temple

For foreign travellers, modern tea ceremony with its precise movements can feel a bit daunting. What do you ideally want your guests to experience when they participate in a tea ceremony?

Every culture has its unique aspects and I think visitors should experience chanoyu at least once. But I think it’s important to choose an experience where they can feel comfortable. After all, chanoyu at its most basic is about enjoying a moment in time with others.

I think there’s a responsibility on the part of the host to talk through the basic steps for visitors less familiar with chanoyu. For example, encouraging guests to sit comfortably on the tatami (rather than in the formal seiza kneeling position), explaining why the utensils are thoroughly cleansed, why the powdered tea is whisked to a certain consistency, why the accompanying sweet should be tasted before taking the first sip, etc. I think this will help the guests to relax, enjoy and learn.

As mutual respect is an intrinsic part of tea ceremony, the guest also plays a role. I’d encourage visitors to comment on one aspect of the experience which particularly moved them, and in doing so express their appreciation to the host.

Can you tell us how the tea ceremony evolved in Japan?

Tea first arrived in Japan from China in the ninth century. Over the centuries, the temples here in Nara started providing tea to visitors as a form of medicine. Modest rest houses near the temples emerged, encouraging visitors to stop and have tea. Over the 12th-15th centuries, tea started to become popular among the aristocracy, scholarly and warrior classes.

Tea entered a new period in the 16th century in the city of Sakai (in present-day Osaka Prefecture), a prosperous cultural centre and trading port. Increasingly, tea became fashionable among wealthy townsfolk and traders and many specialist tea practitioners emerged. Japan’s most famous tea master, Sen no Rikyu (a Sakai local who had been studying Buddhism and tea), created a revolutionary new form which consolidated a number of elements into a new approach – combining tea culture, Zen Buddhist concepts, simplicity and tranquillity, the arts of flower arrangement and incense, and the principles of harmony, humility and respect. He later became tea master to Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, two of the great three unifiers of Japan.

One hundred years later, Sen no Rikyu’s descendants established the three Senke tea schools in Kyoto which had a lasting impact on Japan’s chanoyu culture. The Meiji Restoration in 1868 subsequently dismantled Japan’s hierarchical feudal system and brought the ceremony to a broader population.

Photo Credit: Nara-Jikoin Temple

What is the link between the tea ceremony and Zen Buddhism?

Undoubtedly the tea ceremony has been strongly influenced by Buddhism, ever since its arrival in Japan and adoption by Japan’s first temples. ‘Cha zen ichi mi’ is an idiomatic expression associated with Sen no Rikyu and means ‘Tea and Zen have one taste’. The aesthetics of the tea ceremony are synonymous with the aesthetics of Zen Buddhism.

At its simplest though, I think the Buddhist view that we need to live harmoniously and respect all living things is integral to tea ceremony. We need to consider others, have regard for others. It’s the same with tea – we come together to share a special moment in time with others. To stop, reflect, share thoughts on our lives. It helps improve our relationships and connection.

We understand Jikoin founded the Sekishu-style of tea. How is this different to other styles?

Yes, there are many different styles of chanoyu which developed since Sen no Rikyu’s time. The Sekishu-style originally practised at Jikoin was buke-cha, a style of tea enjoyed by members of the Tokugawa warrior class who studied tea as part of their training in self-discipline and refinement.

Personally, I don’t favour the overly rigid form of tea which emerged in the century after Sen no Rikyu’s death. In my opinion, this is when the focus became more about exacting rituals and the teaching element, and less about providing true hospitality to the guest. Perhaps an example is the Osaka approach to tea, which emerged in Sen no Rikyu’s Sakai days, where conversation, relaxing and spending time together was the key focus.

Photo Credit: Nara-Jikoin Temple

There are a number of key tools or utensils used in tea ceremony, such as the tea bowl, tea whisk and bamboo scoop, which are often highly prized works of art in themselves. Do you have any particularly special utensils at Jikoin?

To be honest, not really! I think our most prized possession is the place itself. Jikoin’s founder created the whole site as a ‘tool’ for the purpose of tea. With such a wonderful place, you really don’t need anything else. No need for special utensils. I think this is also consistent with Sen no Rikyu’s philosophy – he valued the beauty of everyday items over the flashy and ornate.

Perhaps the other ‘tool’ that’s important is the ability to engage with your guests. Like the hospitable merchants serving tea in Sakai where Sen no Rikyu grew up, I like to talk with my guests. I think that’s an integral part of tea and its omotenashi. I also try to spend an hour outside in the morning tending to the garden. As head priest and host of the guests who come to enjoy our tea, it’s important for me to feel genuinely connected to the environment I create for the experience – another expression of that omotenashi spirit.

Photo Credit: Nara-Jikoin Temple

Can you tell us what you like most about living in Nara Prefecture and at Jikoin?

One of the special aspects of Nara is its nature. There’s a deep reverence for the natural world here which stretches back to ancient times, even before Nara became Japan’s first capital. The ancient people who lived here worshipped the natural environment, believing spirits inhabited the mountains and forests. Shinto shrines were eventually built on these sacred sites, followed by Japan’s very first Buddhist temples. This meant that as the country developed, Nara was kept largely preserved. It has kept its original geography and those ancient sites and buildings.

The same applies to Jikoin. For over 350 years, we've managed to hold onto this special spot. The temple is still surrounded by the original woods and the buildings remain intact. I hope that anyone who visits, regardless of nationality, religion or belief, can feel the power of this sanctuary too.

How To Get Here

Nara is easily accessible by train from both Osaka and Kyoto, the key transit points for a visit to the prefecture. The nearest airports are Kansai International Airport (KIX) or Osaka International Airport (ITM), both located in Osaka Prefecture and which take up to 1.5 hours by airport bus or train to Nara City. Once in Nara, Jikoin Temple is a 15-minute walk from Yamato Koizumi Station on the JR Yamatoji Line, or five minutes by taxi.