Hi Miyata-san! Thanks for taking the time to speak to us. For many in Japan you’ve become the ‘Matsuri Man’ after the documentary of you on TV but could you start off by telling us a little bit about yourself?

Hello! My name is Nobuya Miyata and I work with Asitaski, an organisation that looks to preserve Japanese heritage and traditions. My job mainly involves things like repairing the ‘mikoshi’ heavy portable shrines that are carried during festivals, and building ‘kamidana’ altars - things like that. However, I’m also very involved in protecting and promoting the cultural heritage around ‘matsuri’ festivals, Japanese shrines and Shinto culture. I’m always looking for new ways for young people, overseas visitors and international students to come into contact with Japanese traditions.

I guess most notably in 2014, I held a traditional ‘mikoshi’ shrine procession across 6 european countries (France, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Slovenia, Bulgaria) with a ‘mikoshi’ made by my grandfather.

Wow! We’d actually heard that you started off by studying Biological Resources at university but where was it that you learned all the skills needed for what you do now?

My family - the Miyata family are descended from generations of specialist carpenters. My father was born in Tokyo and my great-grandfather was a carpenter specialised in religious buildings but the business went bust right around the same time our family home was destroyed during World war 2. It’s hard to say exactly as all of the family records were destroyed but it’s generally believed that my family were brought to Tokyo (or Edo back then) from Miyazaki in Kyushu by the then Shogun during the Edo period. I can remember learning the basics of how to use all the tools from a young age when I would always be coming and going from my dad’s workshop.

Then, when I grew up and left home, I decided to polish those skills through self-study and turn it into a job.

My father passed away in 2011 and it was two years after that that I decided to go solo but, though our exact specialisms were different, I knew I had to preserve and pass forward the traditions of my ancestors and my dad’s way of life to a new generation. There have been some tough times but I’m still here doing the same job today.

How many ‘mikoshi’ shrines do you think you’ve carried in your life up until now?

I would say something like 500.

You mentioned before that you’ve not only carried ‘mikoshi’ in Japan but abroad, too. What was it that kicked that all off?

Do you bring the ‘mikoshi’ with you from Japan?

The ‘mikoshi’ tour I did in Europe was a direct consequence of the 2011 Great East Asian Earthquake and Tsunami. I was providing support for ‘matsuri’ festival celebrations in the Tohoku area when I found out about a French NPO that was providing help to the oyster industry in Tohoku - it was a relationship that started in the 1970s when the oysters in Europe were diseased and in danger of dying out, so Japanese fishermen helped provide aid. Hearing the story, I wondered how we could express Japan’s gratitude to the West as well as relay the resilience of Japan’s spirit in the face of the disaster and thought that hosting a ‘matsuri’ festival with ‘mikoshi’ and everything could be perfect. We sent the ‘mikoshi’ on its way to the hometown of the person from the French NPO and we did it!

The ‘mikoshi’ shrine is still being kept safe in the city of Montréjeau to this day.

Is there anything in particular that you would like anyone participating in a ‘matsuri’ festival to know?

My dad used to have a lot of little phrases but one of them was “The best parts of a mikoshi will never be lifted up by just one person”. When I was younger I didn’t really understand the full meaning of this and often thought about it but it’s only now, having experienced so many different ‘matsuri’ festivals and met so many people that I’ve come to understand what he was trying to say - that as long as you have friends at your side, the ‘mikoshi’ can always be lifted.

Doesn’t matter what kind of place, doesn’t matter what country - as long as you and those around you are supporting each other you’ll always be able to put on a fantastic ‘matsuri’, and continue to preserve the traditions that we’ve had from since time immemorial.

I hope people can use that part of ‘matsuri’ philosophy to learn the importance of the connections between people and the importance of supporting each other, and that they can also fundamentally apply that to their day-to-day life.

Is there a particularly strong memory you have from one of the many ‘matsuri’ festivals you’ve participated in over the years?

Oh, I have so many but I think I’ll tell you about the day we were finally able to hoist up a ‘mikoshi’ that hadn’t been able to be used since the 2011 disaster.

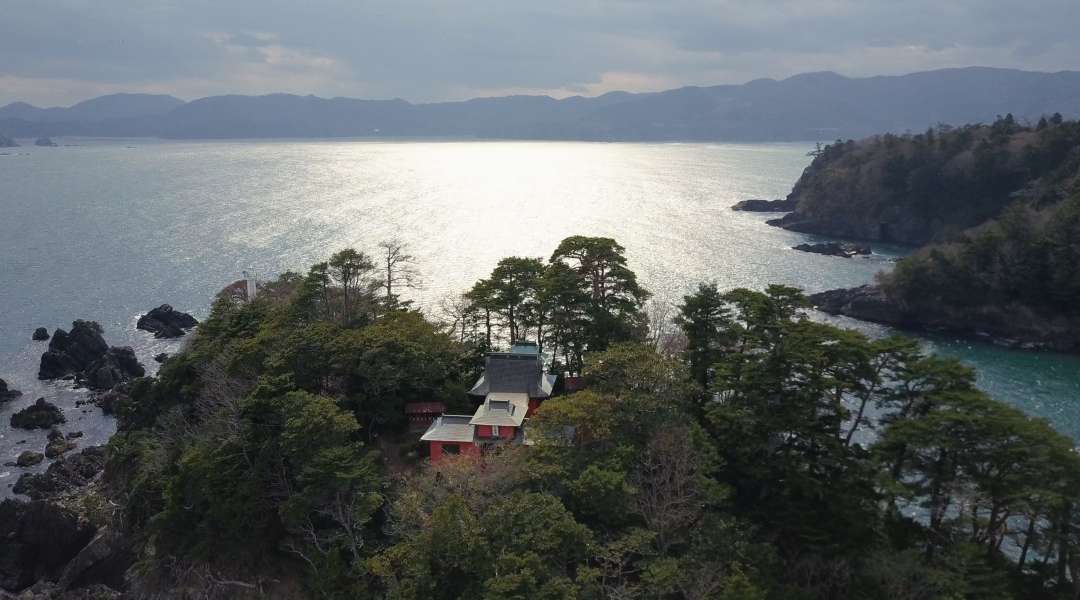

The damage from the 2011 tsunami was overwhelming, and some of these small fishing villages around the Ishinomaki area in Miyagi, with remote shrines that aren’t even on the map, weren’t able to perform the usual ‘mikoshi’ procession that they would otherwise have been able to.

But the fishermen of the village were absolutely set on recovery post-disaster, and got moving, deciding that real recovery couldn’t happen until they’d brought the village together with a memorable ‘matsuri’ festival. I was involved in helping them repair the ‘mikoshi’ and also helped them carry it.

When the day came, the weather was amazing and even the people who had distanced themselves from the village after the disaster came back for the festival, surrounded by the warmth of the atmosphere.

What really moved me in amongst all of this was one particular moment. It was springtime when the festival was held and around midday after the ‘mikoshi’ had finished its procession around the village, it was placed down to rest and the people of the village began a traditional dance called the ‘kagura’ in front of it. This village is also known as Kaze no Tani or ‘The Valley of the Wind’, for obvious reasons, and in the very moment that the kagura dancers finished the final part of the performance, an almighty wind blew through the town bringing with it floods of cherry blossom petals. It was such a powerful moment of beauty that I cried. I cried, and I felt instantly that this was it - this was the landscape, the traditions that the people of this village had been longing to protect.

And yet at the same time, there was a sense of fragility that this might all one day disappear. The impact that that day has had on me continues to be a big motivating force for me to pass on Japan’s heart and it’s beautiful landscapes onto the generations to come.

What a powerful story. Thank you so much for sharing that with us.

You’ve done a lot in your time and accomplished a lot but is there anything in particular you would still like to do?

My one, small dream is to go back to my hometown where they still lift my father’s ‘mikoshi’ every year and follow behind with my children, hoisting my own ‘mikoshi’ and ask them if they will continue the legacy by hoisting another behind mine when the day comes.

In order to make that dream come true, I have to come together with others like me who continue to bear the tradition of Japanese ‘matsuri’, send out the ‘matsuri’ message to the world, and build the foundations so that the next generation can value ‘matsuri’ festival culture and what our ancestors left behind as a treasure of humankind, not just in Japan but also abroad.

In order to make that dream come true, I’m going to have to continue introducing the wonders of the ‘mikoshi’ to the world and putting in the work to build bridges between Japan and the rest of the world.

This month we’ve been looking at the concept of ‘ikigai’ or the reason that you get up in the morning, what you feel gives life meaning. What is your ‘ikigai’?

For me, ‘ikigai’ is, unsurprisingly, ‘mikoshi’. I’ve been able to make so many new acquaintances and do a job that I really am passionate about in a great many number of environments. As I continue honing in on ‘mikoshi’ and ‘matsuri’ culture, I really feel that I’ve found my role in life.

Mikoshi and matsuri are deeply related to Japan’s native religion of Shintoism and in Shintoism there’s something called ‘nakatorimochi’. It sort of explains the role of people who work at shrines but it's a way of thinking that describes how people at shrines give themselves up to stand in between humans and the gods enshrined there in order to protect the gods and also to tell of their power.

I’m not one of those people so it might be a little inaccurate but I sometimes feel like I’m here to sense the direction that the culture around ‘mikoshi’ is heading towards and do what I can from the position of a human being. I feel like the spread of mikoshi culture in the West and all of the other miraculous occurences of mikoshi culture in different places are happening because this being that is the mikoshi is using me to do so.

When I’m chasing each of these miracles and instances of interest, when I feel like I’ve been able to do something to help in the development of Shinto traditions even a little, that’s when I feel ‘ikigai’ and, essentially, the meaning of life.

What is at the essence of what is so great about ‘mikoshi’ for you?

It really comes back to that phrase my father used to use. I interpret it to mean that together we can do great things but I think it’s also what makes me proud to be Japanese and the fact that I’m able to help pass on this legacy alongside people around me. Unfortunately it was cancelled because of everything at the moment but I was actually meant to be in Berlin for the fifth year in a row. The connections with new people and new cultures just keep multiplying. You can make real lifelong friends doing what I do and that is a treasure above all else.

This year a lot of masturi festivals have been cancelled because of COVID but how have you been spending this summer so far? We’d love to see you come to the UK to do something here, too, but do you have any plans?

Everything was cancelled this summer, so I’m investing time and effort into the daily parts of my job and cleanliness and hygiene at shrines and things. I may not be able to join matsuri with all my friends but I can prepare for the day that I can raise a ‘mikoshi’ once more.

I’m hoping it can be a precious period where we can use the time we spend cleaning the shrine and talking to each other in order to find new ways to pass our legacy forward. We don’t have any concrete plans for the UK right now but I do have friends who came over to Japan from Oxford Brookes University. They actually came to a lot of matsuri all over Japan and held the ‘mikoshi’ with me when they were here. They’ve also said it’s their dream to see a proper ‘mikoshi’ come to the UK for a procession so I’d really like to make that a reality someday.

Is there a particular matsuri that you would recommend to someone visiting Japan, or a top tip for someone planning on participating?

There are around 100,000 shrines in Japan and if you count festivals that operate around temples and other things there are maybe over 300,000 matsuri festivals throughout the year. There’s so much tradition contained in each and every one of the festivals so choosing just one feels like it doesn’t show how all they all shine in their own right, but one particularly characterful matsuri festival is in Furukawa in Gifu Prefecture - the Okoshidaiko festival. On the second night of the three day festival, they have a massive procession of huge and small taiko drums that weave in and out of the town’s winding streets. Seeing a sight like that really gives you an appreciation of how incredible Japanese matsuri festivals can be.

That said, the matsuri that I really love from the bottom of my heart is the matsuri from my hometown. Running around the town as a kid, chasing the ‘mikoshi’, getting involved in the festivities with my friends, are absolutely irreplaceable experiences. There are loads of really fantastical performances and celebrations within Japanese matsuri festivals and each and every matsuri evokes a strong sense of local pride for many of the people who live there.

By experiencing first hand that idea of protecting and preserving something that means a great deal to them I think is one of the best ways to experience the true beauty of Japan.