Masters Series Part Three: The Art of Calligraphy

Arriving in Japan in the 6th century, the art of calligraphy has been used and adapted over centuries, becoming a prolific and beautiful art form seen and practised throughout the country. Here, we speak to the founder & director of Fukumitsu Calligraphy School, Keiko Fukumitsu, who has lived and breathed calligraphy for most of her life.

A former Japanese Calligraphy major at Nara University of Education and lecturer at the Center for Japanese Language and Culture at Osaka University, Keiko is also the director of a number of non-profit organisations that promote calligraphy in Japan and overseas. Having taught both in Japan and internationally (including in Australia), Keiko gives us an insight into the history, how the art is practised in Japan today and what she loves most about living in her hometown of Osaka and the broader Kansai region.

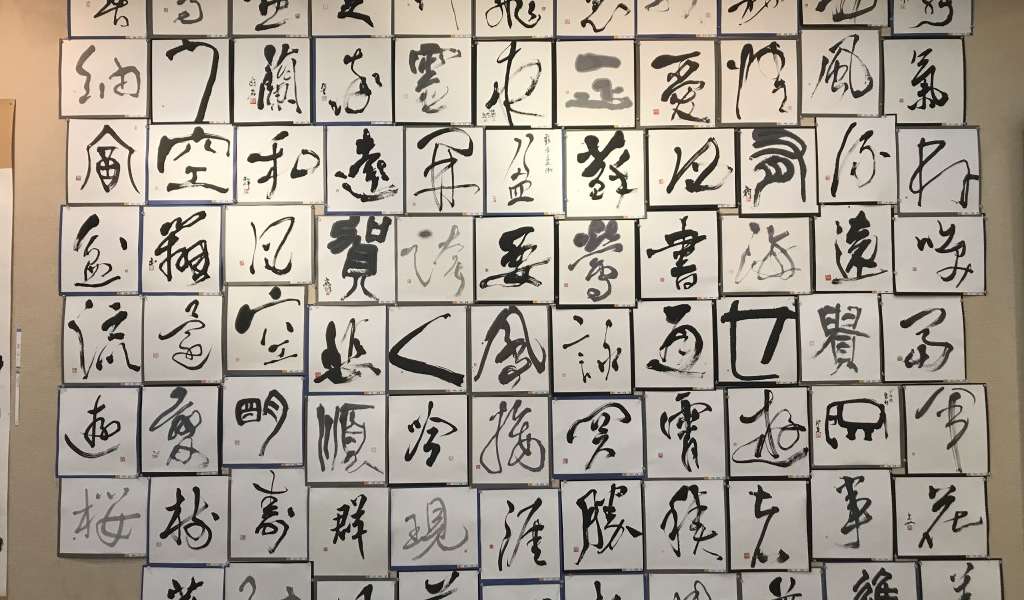

Display of single character works by different artists

Can you tell us a little about the history of ink and brush calligraphy?

Calligraphy originated in China, where, around 3,500 years ago, basic pictographs started appearing as oracle bone and tortoiseshell inscriptions. These primary characters evolved to become more stylised, and by the end of the 4th century, there were 5 basic forms, ranging from block styles with clearly defined strokes to more cursive, joined-up styles. Over time, the practice to render characters in ink on paper to record or communicate information took on increasingly artistic and spiritual dimensions as the form spread among China’s literati and religious groups.

Calligraphy arrived in Japan from China in the 6th century, along with Buddhism. Japan had no written language at the time, and the Chinese characters (known as kanji) were adapted to Japan’s spoken language. A new simplified form (known as kana) was also created from those characters to represent Japanese linguistic elements. The standard written script we use in Japan today is therefore based on characters from those ancient times.

Practicing characters at a shodo school

What is shodo and how is it practised in Japan?

In Japan, the art of writing characters on paper with brush and ink is known as shodo (literally meaning the ‘way of writing’). For centuries, it was considered an essential way to understand classical literature and Buddhist beliefs and as a way of developing mental discipline.

Today, you’ll find it practised in many ways in Japan. You’ll find exhibitions of shodo works, whether by beginners or highly credentialed practitioners, young kids having fun with big character works or older citizens, on show at any time throughout the year in schools, public spaces and galleries across Japan.

You’ll also find it’s taught widely across Japan. Students study shodo for six years as part of the national curriculum. There are also private shodo schools that operate after school and on weekends and teach both children and adults – there are many people in Japan who are keen to improve their writing and brush skills, find some quiet time to sit and focus, or connect with art and ideas.

There’s a New Year custom called kaki-zome, where we write characters to represent our personal hopes or resolutions for the coming year. It’s something fun to do as a family, and school groups will often visit local temples or shrines in January to write their aspirations in ink. Each December, the head priest of Kyoto’s Kiyomizudera Temple also releases the ‘Kanji of the Year’, which captures the nation’s mood based on nationwide polls.

Having fun with large brush works

What inspired you to take up shodo and dedicate your professional life to the study and teaching of shodo?

My interest in shodo began when I was about 10. I joined a calligraphy school to learn more about shodo, and when it came to university I decided to major in Japanese calligraphy. I was always interested in the history of art and art theory. While I was at university, I worked part-time as a calligraphy tutor and was fortunate to have quite a few students by the time I graduated. It seemed like a natural progression to open my own school. For around 40 years, I have been running my own school as well as teaching at university, refining my own practice and exhibiting works. I also participate in a number of international programs that aim to introduce shodo to overseas audiences in Australia, Southeast Asia and Europe – this, in particular, is one of my passions.

What do you think international students like most about learning shodo?

In many ways, it depends on the student – their age, level of experience, motivation and whether they’re students of Japanese or not. But I do generally find that international students enjoy learning shodo because it’s an opportunity to find out about many other aspects of Japan, such as our history, art and literature, traditions and our cultural ties with China. Some students are also attracted to the spiritual aspects that have long been associated with shodo, such as Buddhist beliefs and thoughts.

I find international students often enjoy that shodo requires a lot of concentration. Once you’ve made a stroke, it can’t be redone, which means you need to focus to create a visually pleasing character. How you control the brush, use the ink and position the stroke all need to come together at the same time.

Primary school children with their shodo

What are some of the key differences in brushwork between shodo and western approaches?

There are a few key differences. Firstly, as mentioned before, it’s not possible to go back and re-do a stroke. A character is formed by brush and ink in the moment and cannot be changed. However, in many western art forms, you create a work by applying layers and touching up the work.

Then there’s the concept of ‘empty space’. In shodo, the space around the written characters is just as important and beautiful as the characters themselves. The eye should be drawn as powerfully to the untouched white space as the black. We also sometimes play on this space in the way we apply the ink, creating strokes where the ink appears to run out and allowing the white of the paper to show through. This is also regarded as part of a work’s appeal, if naturally and artistically expressed.

Shodo is so nuanced, and to become fully competent in it, a student needs to constantly practise over a number of years. They need to learn the five main styles, refine their brush technique, their character spacing, the application of ink on paper and the control of their hand and mind. Over time, a student’s ability to artistically render the characters becomes second nature and their compositions are produced without conscious effort. This is when their individual style and creativity shine through.

Red seals are often visible on works of calligraphy. What is the meaning or purpose of these seals?

The seals act as a sort of signature for the artists. They are officially considered part of the art of calligraphy. Many artists have a range of seals in numerous shapes and styles, created by calligraphers who are specialised in the art of seal engraving (known as tenkoku). From an aesthetic point of view, the vermillion-red of the seal also brings a contrasting beauty to a black and white composition, though some more delicate works, such as those made with kana characters, are not stamped as this could upset the work’s fine balance. And, in older times, particularly treasured works would be stamped by the owner as a form of certification as works were passed down through the ages. So don't be surprised when visiting museums to see classic works with a whole lot of seals!

You were born and brought up in Osaka. As your hometown, what do you particularly like about living there?

It’s a very practical response, but I love how conveniently located it is. Osaka lies in the middle of the Kansai region, so it's close to the traditional cultural hubs of Kyoto and Nara, as well as Kobe. There’s always a lot happening in the art world in this part of Japan, meaning I can easily attend exhibitions and gatherings of shodo artists and educators.

Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts ©Osaka Convention & Tourism Bureau

If visitors to Osaka and the Kansai region wanted to see displays of shodo works, where would you recommend?

To see classic works from older times, I suggest the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts. There’s also the recently opened Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka. Visitors can also find exhibitions by shodo artists in some of the smaller private galleries around Osaka (Oimatsucho, in Kita Ward, is one area you'll find such galleries).

Nara City Museum of Calligraphy in Honour of Kason Sugioka exhibits more recent and contemporary works. If you visit this museum, I'd recommend stopping by the small specialist brush and sumi ink shops around Nara’s Sanjo-dori Street – Nara produces Japan’s best sumi ink sticks. I spent my university years in Nara, and for those who enjoy history and local culture, Nara’s old backstreets are an excellent place to base yourself for a few days. Like Kyoto, Nara is a former capital but somehow has retained an ancient spirit and a quiet sense of older times. Even talking about it brings back evocative sights and smells for me… particularly the sacred forest that backs the city and envelops special treasures like Kasuga Taisha Shrine.

Of course, there are also many short cultural experiences in Japan introducing travellers to aspects of Japanese culture such as shodo, ikebana and tea ceremony. For people with a particularly keen interest, shodo schools offer the opportunity to engage more deeply and learn about the history and practice of the art form.

Kasuga Taisha Shrine, Nara Prefecture

How to Get There

As one of Japan’s major hubs, Osaka is easily accessible from across Japan and located on the main bullet train line between Tokyo and Hiroshima. It takes between 2 hours, 30 minutes (Nozomi) or 2 hours, 50 minutes (Hikari) from Tokyo by bullet train. Osaka is also easily reached from Kyoto, Nara and Kobe by a number of JR and non-JR regional lines. The closest airports are Kansai International Airport (KIX) and Osaka International Airport (ITM) in Osaka Prefecture. From KIX, it takes 30-50 minutes by JR Limited Express Haruka to different points in central Osaka. From ITM, it takes around 20-25 minutes by monorail/JR train or bus.

Contact Details for Fukumitsu Calligraphy School:

Email: kfolac@gmail.com

Address: 4-3-15 Minamihorie, Nishi Ward, Osaka 550-0015